Introduction

The outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus (severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2), prompted a global heightened awareness of hand hygiene, with a specific focus on proper handwashing and the use of hand sanitisers to limit the spread of the virus. Considering the dramatic increase in the usage of hand sanitisers among South African consumers, the need was identified to develop a better understanding of South African consumers’ usage behaviour and perceptions regarding hand sanitisers, but also to assess their knowledge about its proper use.

In April to June 2021 the Bureau for Food and Agricultural Policy (BFAP) and the Plant Pathology Division within the Department of Plant and Soil Sciences at the University of Pretoria, conducted primary consumer research among a socio-economically disaggregated sample of 830 consumers, with three sub-groupings: low-income, middle-income and affluent consumers. This article presents key results from this survey, with a specific focus on hand sanitiser purchasing behaviour, brand preferences, typical hand sanitising frequency, product consistency preferences, hand sanitising behaviour when shopping, the perceived importance of hand sanitiser product attributes and consumers’ perceptions regarding hand sanitisers.

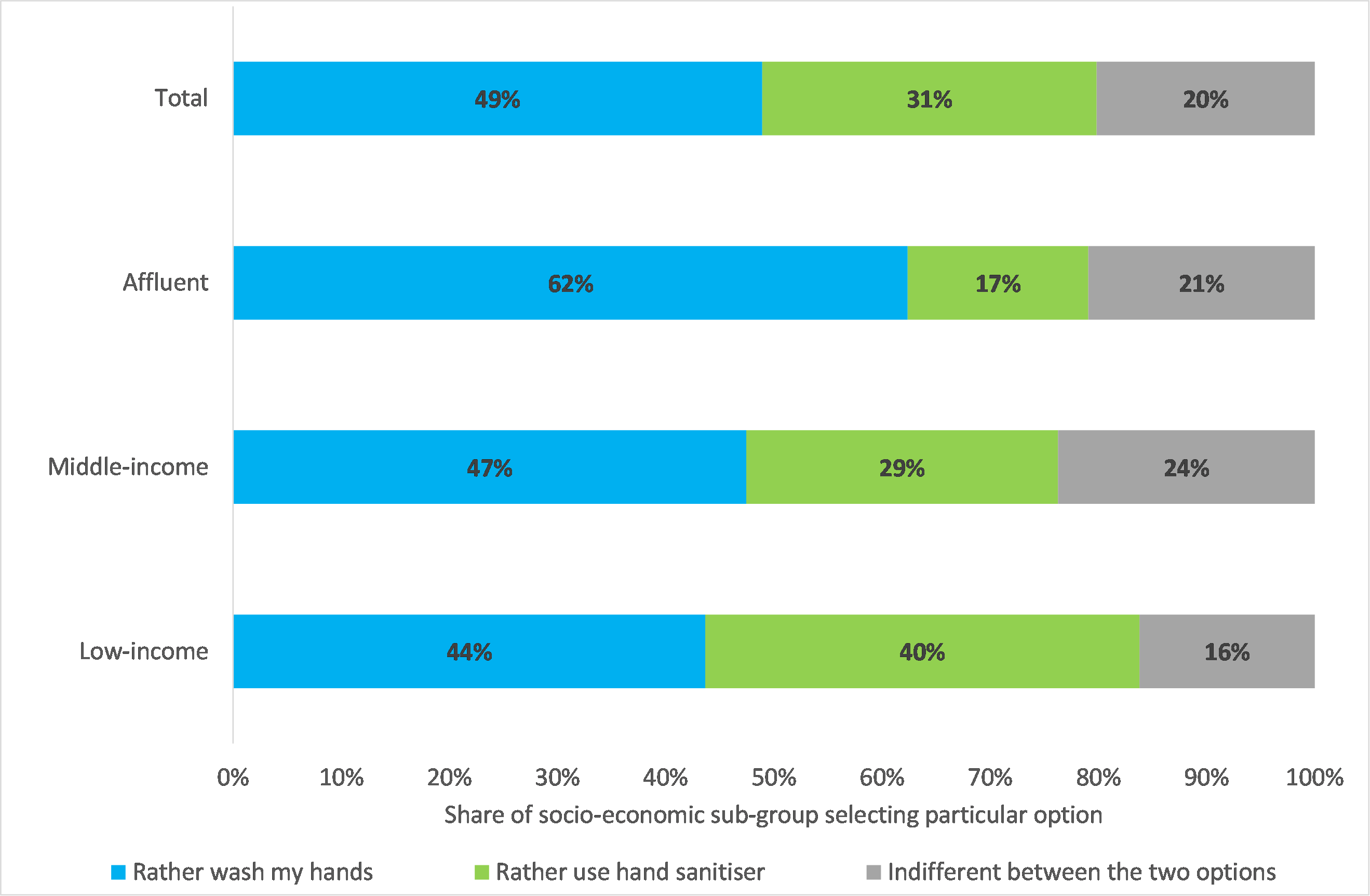

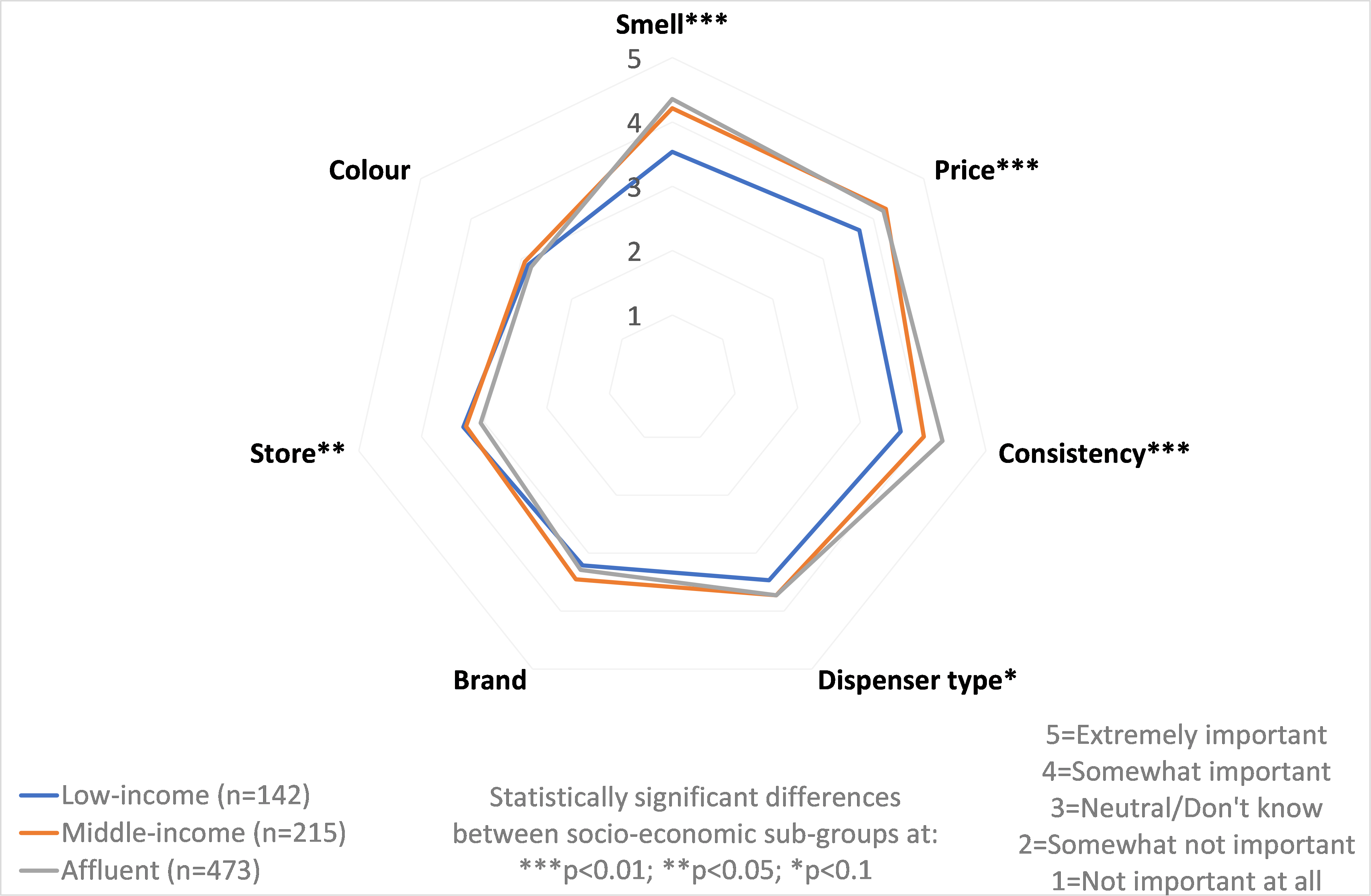

Do consumers prefer handwashing with soap or using hand sanitisers?

|

Figure 1: Preferences for handwashing versus hand sanitiser

(Source: Survey results)

|

- Handwashing with soap was the overall most preferred option (49% of sample), followed by using hand sanitisers (31%).

- Affluent respondents were more drawn to washing hands with soap, while low-income and middle-income respondents revealed a dominant preference for using hand sanitiser (statistically significant differences between the three socio-economic sub-groups at p<0.01).

|

Most respondents (80%) wash their hands more often at present compared to before the COVID-19 pandemic.

Hand sanitiser purchasing behaviour

|

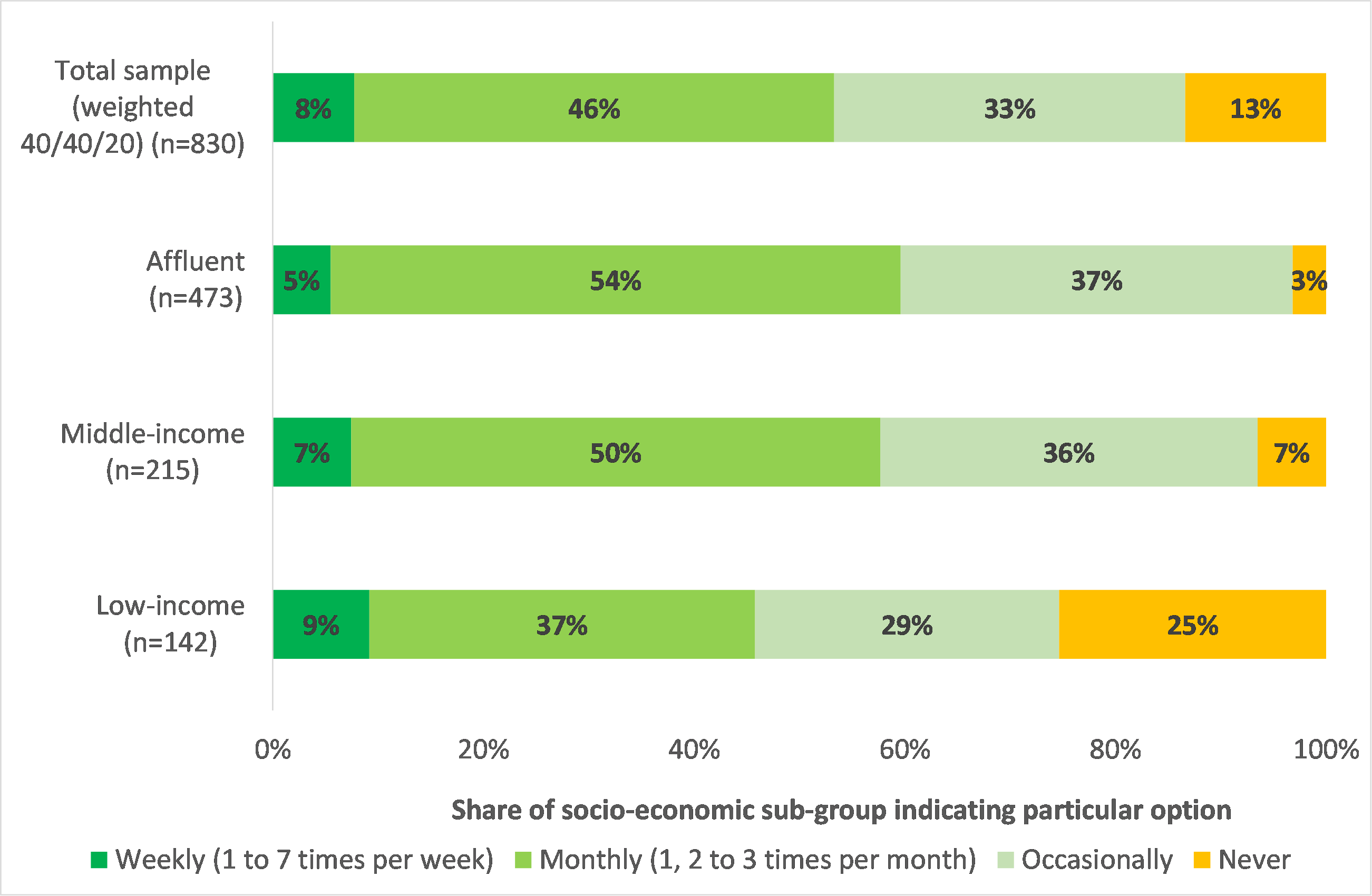

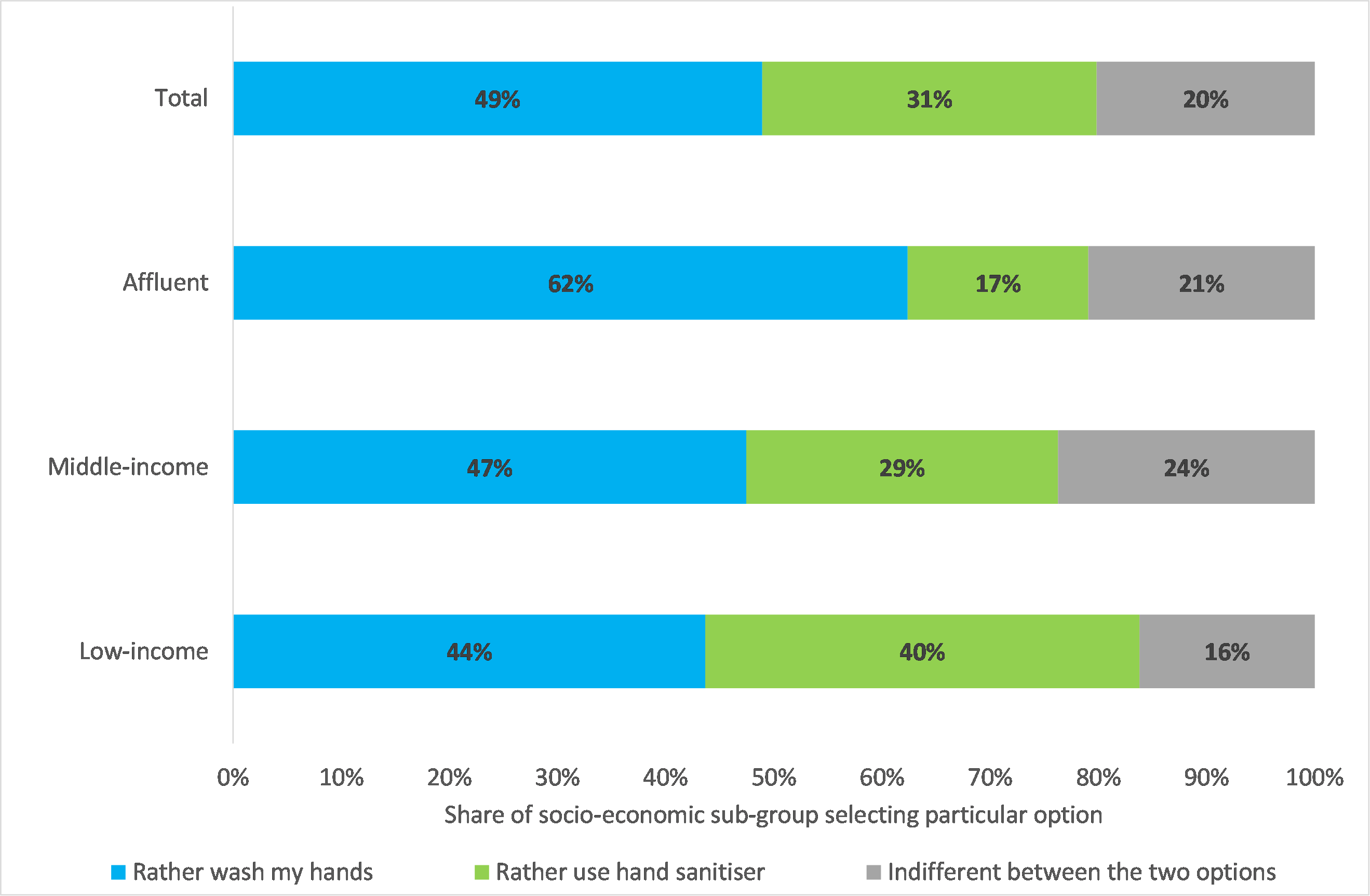

Figure 2: Typical hand sanitiser purchase frequency

(Source: Survey results)

|

- 46% of respondents typically purchase hand sanitisers monthly, followed by 33% occasionally.

- Statistically significant differences between sub-groups, with more frequent purchasing among middle-income and affluent respondents and a relatively larger share of low-income respondents never purchases hand sanitisers.

|

Across the socio-economic spectrum, the dominant hand sanitiser purchase locations were large chain pharmacies and retailer chain stores.

Hand sanitiser brand preferences

Strong brand preferences were limited, with only 18% of the total sample ‘always’ preferring a particular hand sanitiser brand. The majority of the sample (55%) did not have any specific hand sanitiser brand preferences. Preferring a specific hand sanitiser brand (‘always’ or ‘sometimes’ combined) was significantly more prominent among middle-income and affluent respondents.

Hand sanitiser labelling and legislation

Overall, the occasional reading of hand sanitiser labels was dominant (52% of respondents) followed by ‘never’ (31)%. Only 17% of respondents indicated that they always read the information on hand sanitiser labels. Middle-income and affluent respondents indicated a larger tendency to read the detailed information on hand sanitiser labels than low-income consumers]. The highly technical nature of hand sanitiser ingredient lists could be a limiting factor in this regard.

Respondents’ knowledge regarding specific ingredients of hand sanitisers focused mainly on alcohol (mentioned by 54%), water (28%), ethanol (13%), glycerine (13%) and fragrance/perfume (11%).

When asked about the recommended alcohol percentage in hand sanitisers, a larger number of middle-income and affluent respondents indicated “70% alcohol content’ (62% and 57% respectively) compared to low-income respondents (32%).

On a typical day, how many times do respondents sanitise their hands?

Hand sanitising frequency increased significantly with lower socio-economic status:

| Low-income: 15 times / day |

Middle-income: 13 times / day |

Affluent: 10 times / day |

Several respondents indicated that their hand sanitising frequency depended on whether they left home or not. The less frequent hand sanitising of affluent consumers could possibly be linked to ‘working from home’ conditions, while middle-income and low-income consumers are more likely to not be able to work from home.

Do respondents prefer liquid or gel hand sanitisers?

No strongly dominant hand sanitiser (HS) option was observed, with no statistically significant differences between the socio-economic sub-groups:

| Prefer liquid HS: 38% |

Prefer gel HS: 34% |

Indifferent: 29% |

Hand sanitising behaviour when shopping

|

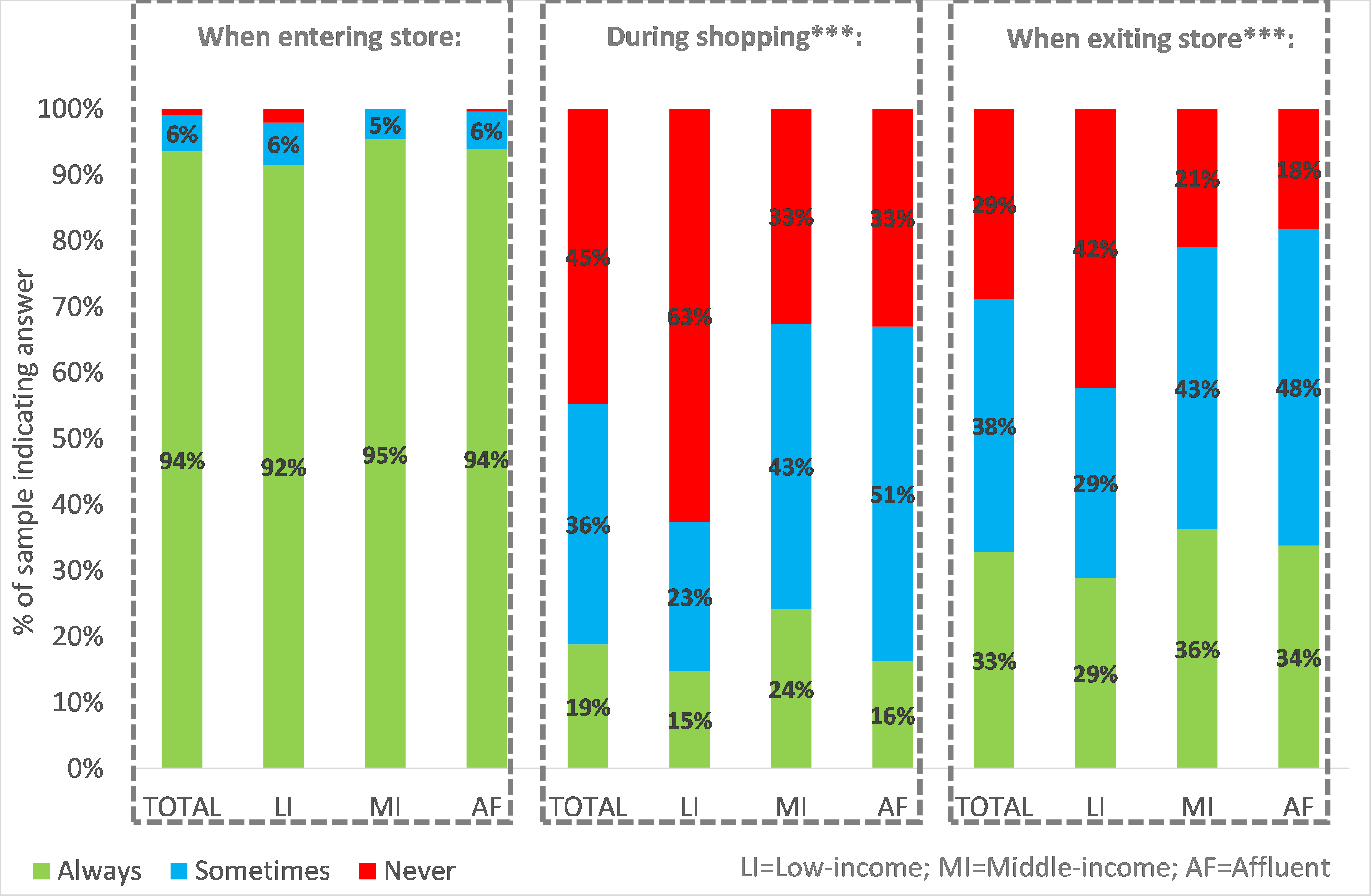

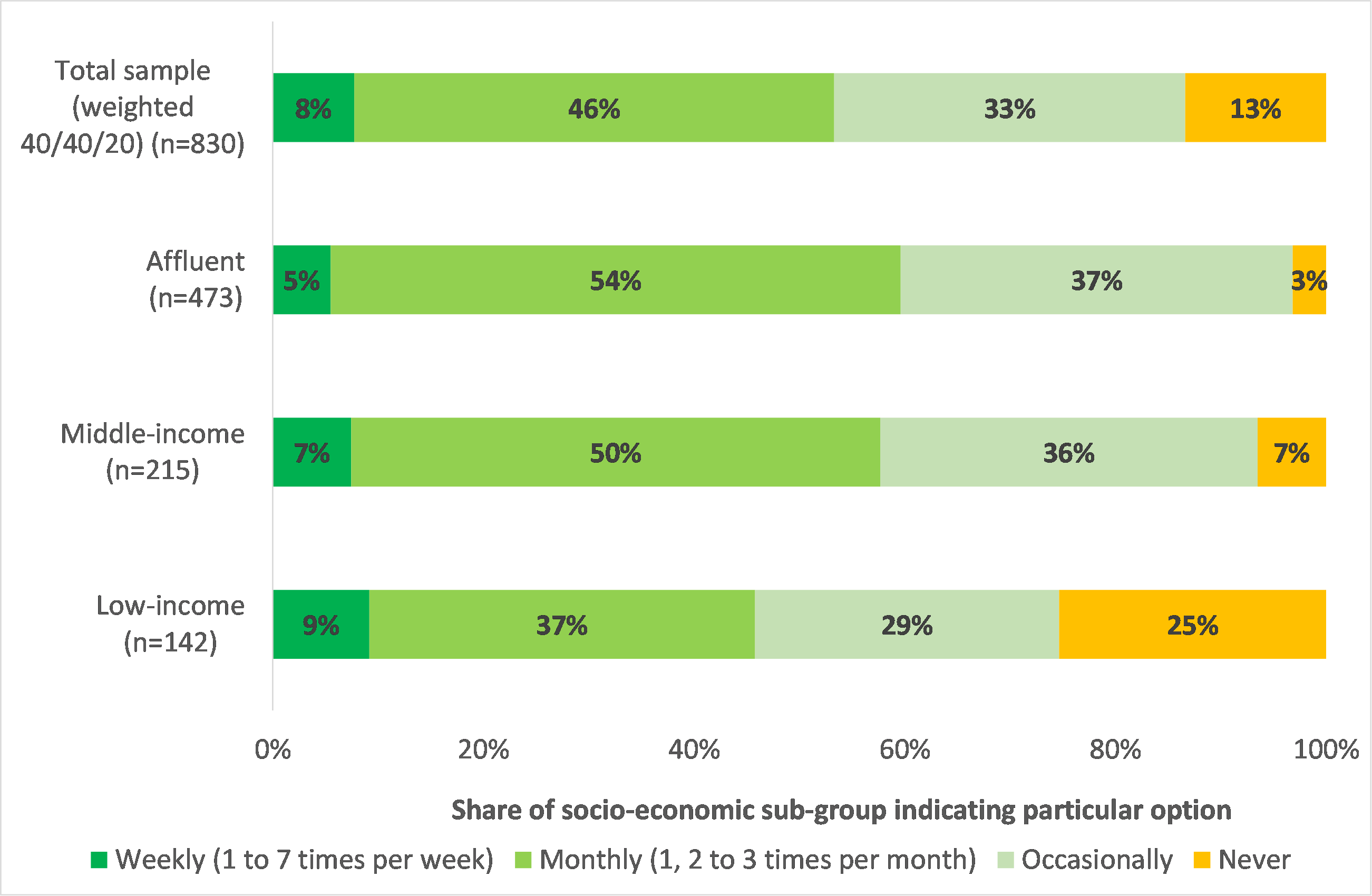

Figure 3: Hand sanitising behaviour when shopping

(Source: Survey results)

|

- Sanitising hands when entering a store is a government mandated requirement.

- Most respondents (94%) ‘always’ sanitise hands when entering a store (no statistically significant differences observed between socio-economic sub-groups).

- Hand sanitising during shopping and when exiting a store were less popular, but significantly more prominent among middle-income and affluent respondents (p<0.01, *** in Figure 3).

|

When shopping, do respondents sanitise their hands with the sanitiser provided by the store or hand sanitiser that is provided by themselves?

| HS provided by store: 56% |

bring and use own: 11% |

Indifferent: 33% |

A statistically significant larger share of low-income respondents (72%) uses hand sanitiser provided by the store, while a significant larger share of affluent and middle-income respondents (46% and 39%) use both options.

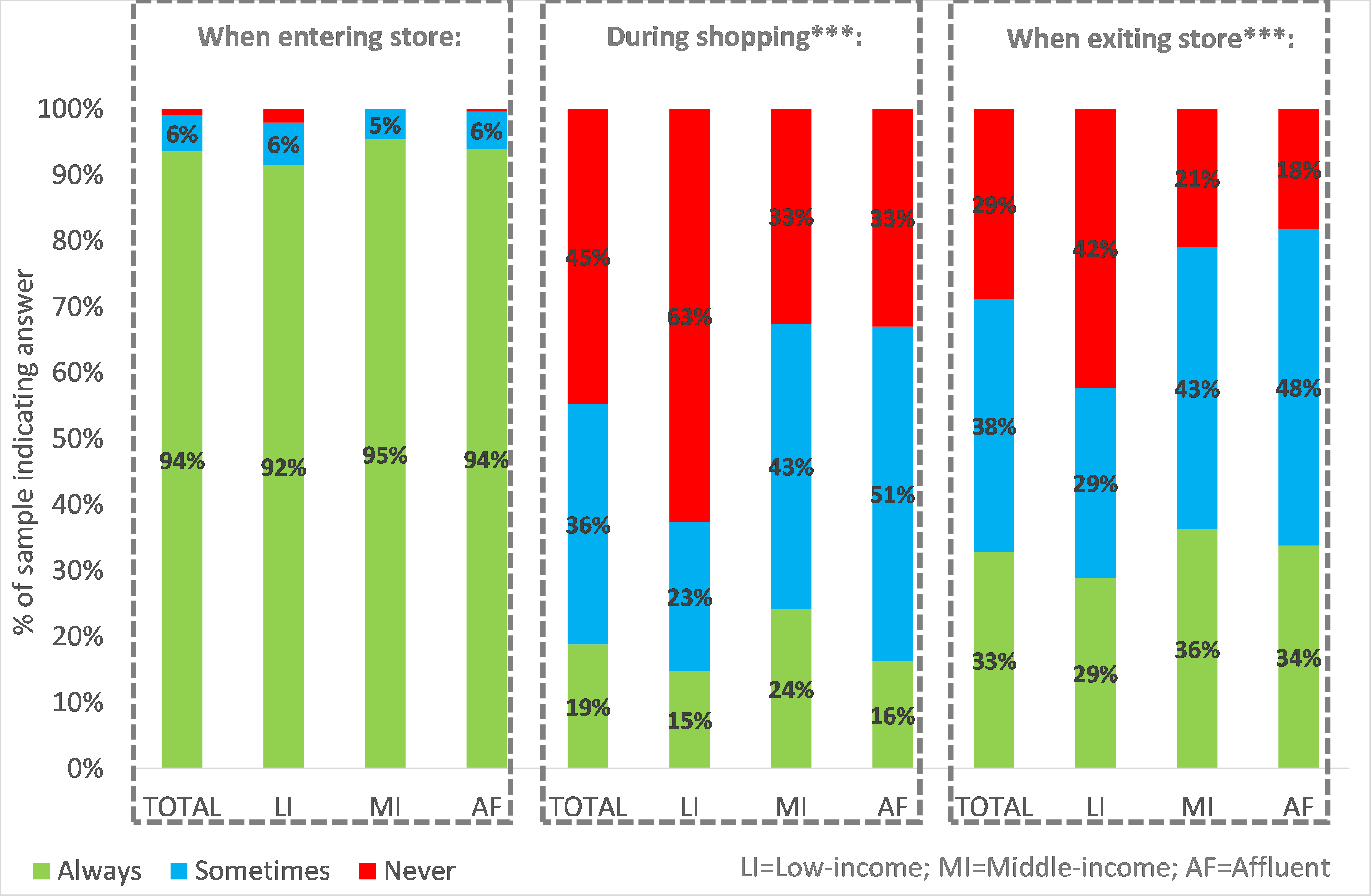

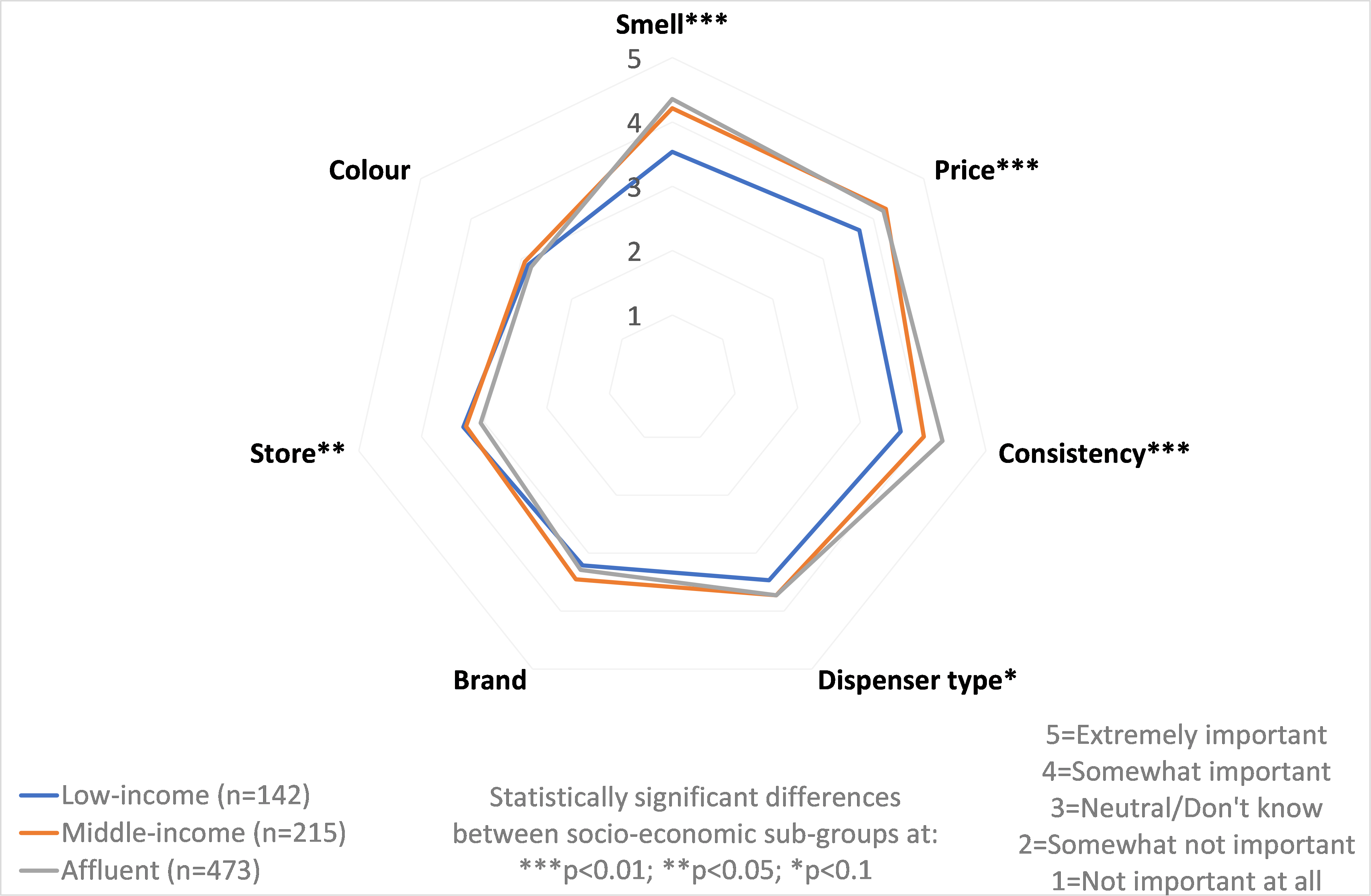

The perceived importance of hand sanitiser product attributes

Price, smell and consistency were the three dominant hand sanitiser attributes valued by consumers. Middle-income and affluent respondents generally valued the various hand sanitiser attributes the most.

Figure 4: Overview of the perceived importance of hand sanitiser attributes

(Source: Survey results)

Consumers’ perceptions regarding hand sanitisers

|

Figure 5: Perceptions regarding hand sanitisers

(Source: Survey results)

|

- Consumers were most positive about hand sanitisers in terms of feeling safe after usage, not experiencing burning skin after usage, liking hand sanitising and the ability of hand sanitiser to keep their hands clean.

- Consumers were least positive about hand sanitisers in terms of the smell of hand sanitisers, affordability, the ability of hand sanitisers to kill the virus and hand sanitisers causing sticky hands.

|

The complexity of consumers’ perceptions and concerns regarding hand sanitisers was evident from respondent remarks such as the following

- “Does the colour of the sanitiser have any effects on the quality and smell of the sanitiser?”

- “Some stores don’t use proper hand sanitisers. It’s a mixture of bleach and water. The smell and sensation on your hands are telling.”

- “Hand sanitisers are medical, functional products. They don’t ever need to be scented.”

- “Harmful ingredients should be banned. Sanitisers should be tested regularly by the government to see whether they contain the correct ingredients and whether they’re effective. I prefer alcohol-free sanitisers or soap.”

- “How does one tell if a hand sanitiser is good or not? Or whether it is effective?”

- “I am not always sure that shops comply with the percentage alcohol in hand sanitisers.”

- “I fear that many sanitisers are not up to standard in terms of ingredients.”

- “I feel like some hand sanitisers offered in public are not of good quality and supplied at a low cost due to so many people using it. I don’t trust some of them, some have a pungent smell, which isn’t good for skin.”

Concluding thoughts

In general, when purchasing and using hand sanitisers, smell, price, consistency (i.e. liquid or gel), product safety and effectiveness are important to consumers.

Consumer education related to hand sanitisers should focus on the recommendations as set out by the World Health Organisation (WHO):

- Consumers should use an alcohol-based sanitiser with an alcohol content of at least 70%, based on effective and fast anti-microbial activity.

- Hand sanitisers should comprise ethyl alcohol (ethanol) or isopropyl alcohol (2-propanol) as the active ingredient; in addition to inactive ingredients listed as follows:

- Water as a diluent;

- Glycerol to prevent drying out users’ skin; and

- Hydrogen peroxide to inactivate contaminating bacterial spores in the solution.

- Hand sanitiser products should preferably not contain perfumes or dyes due to risk of allergic reactions.

- Hand sanitisers should not be stored in a hot car, as the active ingredients may become less effective when exposed to sunlight and high temperatures.

- Hands should be rubbed for 20 seconds after having applied the hand sanitiser to ensure good coverage.

As set out by the South African National Standard (SANS 490:2020) on alcohol-based hand sanitisers, the following information should be indicated on every bottle of hand sanitiser:

- Alcohol content (which should be at least 70% or higher);

- A list of the active and inactive ingredients and the adverse effects they may cause;

- Instructions for use;

- Mandatory warnings; and

- The full address of the manufacturer.

Since sanitising hands when entering a store is a mandatory requirement (and will probably remain so in foreseeable future) retailers need to provide consumers with a more positive in-store experience by supplying quality hand sanitisers that adhere to standards and are free from harmful ingredients. Furthermore, the detailed labelling of hand sanitiser containers supplied in retailers to customers upon entering the store is recommended – providing consumers with critical information as specified by SANS 490:2020.

Authors:

Dr Hester Vermeulen 1, Dr Willeke De Bruin 2 & Prof Lise Korsten 2

1 Bureau for Food and Agricultural Policy (BFAP)

2 Department of Plant and Soil Sciences, University of Pretoria

Acknowledgements:

Project funding provided by the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF)’s One Health for Change programme, the Inter-Academy Partnership (IAP) and the Department of Science and Innovation-National Research Foundation (DSI-NRF) Centre of Excellence in Food Security

For more information please visit www.bfap.co.za.